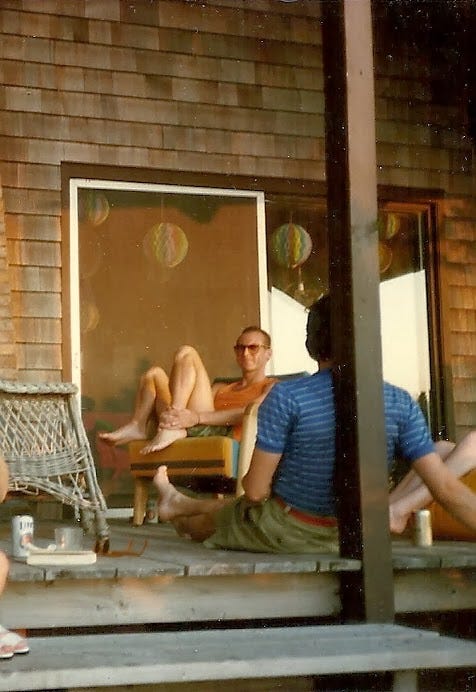

There were five of us—Bruce, Kerri, Pamela, Nancy. And me. We rented a house on the Great South Bay on Water Island, with that sweeping, faceted water right before us. From our deck, the sun set in wide dying flourishes every evening. The ocean, on the other side of the slim island, was a two-minute walk from our house. The beach was one link in the grand line that stretched along the southern flank of Long Island to its very tip. We were on Water Island, a small enclave that was part of Fire Island, just 50 miles from New York City—but another world entirely. It was a kind of miracle, really, that this dreamy place was so near.

Our house. We kept the windows and doors wide open. The clean scents of the island entered and left as casually as we did. Every so often, a light, brackish breeze from the Great South Bay wafted through. Out front, there was Rosa rugosa, with its little beach bum flower that always looked disheveled, as if it had just gotten out of bed. When you put your nose to it, you received a narcotic jolt of rose.

Light everywhere.

If you walked into the house late in the morning, you would encounter the five of us, like a curtain going up at the beginning of a play, in various places around the spacious single room. Kerri on the easy chair with his sketchbook, drawing, but listening. Nancy on a bar stool, slim legs crossed, glasses perched in her hair, laughing. Bruce, standing before the island counter near the open kitchen chopping or slicing something. Me, on the other couch, trying to make everyone laugh. Pamela, just getting up. She’d make her entrance groggily from her bedroom as late as eleven. She slept in a long dark T-shirt down to mid-thigh. She’d stumble toward the coffee.

“I hate mornings,” she’d say. “I’m a real bitch. Stay away from me.” Then a half-hearted rendition of her two-beat laugh. “I’m warning you. I’m serious. I’ll rip your head off.”

She’d pour some coffee, take the cup to the couch and sit. She’d reach for a magazine with her free hand and begin reading. Like Nancy, no make-up. It was a privilege to see them both unadorned.

We’d sit and talk. There was never any shortage of subjects. All of us had our New York lives. Bruce was a lawyer working part time. Nancy worked for a man who advised hospitals on how to streamline their costs. Kerri worked for a jewelry designer. Pamela did various things to get by and probably had some money coming in from her family. I was an advertising copywriter. None of us were married. None of us had children. None of us had any real obligations. Our parents were still healthy then. This happens only once. I know that all so well now, reaching back.

“Bruce, why don’t you become a chef?” I said. It was clear he loved to cook.

“I would,” he said, “if I were good enough.”

“Will you ever practice law?” I asked.

“I sincerely hope not,” he said. He had his law degree from Columbia.

“He’s been offered a job,” Nancy said.

“Oh, really,” Kerri said with arched eyebrows. No one could arch eyebrows like Kerri.

“At the Bank of New York,” Nancy said. “They love him. They want him to work full time,” Nancy said.

“Are you going to take it?” Kerri said.

“You should,” Pamela said. “You’re so brilliant.”

“I hate the law,” Bruce said. “I hate everything about it.”

“But,” I said, “all that education you have.”

“A complete waste,” Bruce said.

“You don’t mean that,” Pamela said.

“Yes. I do,” Bruce said. You could see he didn’t want to hear any more about this.

It was like a family discussion. It was a family discussion. We were a family—the first real family I ever had. I had the beautiful security of being part of other people’s lives. This was something I hadn’t ever experienced. A sense of belonging. Here, in this house, on a summer morning, with these four people, with Kerri, Bruce, Nancy and Pamela, I felt us against the world. I felt—perhaps not in any way I could articulate—that now I truly had a family. And a sense that what I lost, or never had, could be found.

I was grateful then. I’m grateful now.

“Well, I have some news,” Kerri said. He said in his bombshell-dropping way, calmly, with a little sing-song.

“What, what?” Nancy said.

“This better be good,” Bruce said. “I’m in the middle of slicing carrots.”

“I think I’m in love.”

Even Pamela perked up.

Nancy screamed.

“Who? Who is it?” Pamela said, leaning forward on the couch.

“Well—you’ll love this. He’s an orthodox Jew.” Kerri let off a peal of machine gun laughter.

“Who is he?” Nancy said.

“Yes, how did you meet this…rabbi?” Bruce said.

“He’s not a rabbi,” Kerri said. Laughing. “He works for Saks.”

Kerri had a look on his face. The look of someone who had found what he was looking for. That he hadn’t been able to find until now.

We were all exuberant, happy for him. One more of us had gotten there.

The morning unfolded, never lacked the energy of friendship.

Then, at last, someone would call out, “I’m going to the beach. Anyone want to come with me?” The second part of the day would commence. We’d finish whatever it was we were doing. The beach and the ever-surprising ocean was waiting.

We’d gather towels and chairs and straw bags with water and books and lotions and hats. Then, one by one, we’d make our way down the now-warmed narrow boardwalk to where it ended and to where the sand began.

Us.

Youthful memories are so nostalgic! Those were the days!

Beautiful!