Lucien Vitiello died last February. He was 85. He passed away in his hometown of Sanary-sur-Mer in the South of France. He was a man I was lucky to know in the year I spent researching a book in that pretty town on the Mediterranean coast near Marseille.

He was a fisherman. Every morning, before dawn, he would take his small boat, Irène, five or six miles or more out on the Mediterranean in search of fish. I went with him quite a few times on that quest as an observer. I’m sure I was in the way, but he let me come again and again. When we returned, he often gave me some of his prized fish to take home. He was like that.

He didn’t know me from Adam when I first came to Sanary. When I sought out fishermen, because I wanted to learn about their ways for a book I was writing, everyone directed me to him. Lucien was the Prud’homme, or head, of the fishermen’s collective. He was highly respected, even among the fiercely independent, often disgruntled fishermen of Sanary who rarely agreed about anything. No one was ever kinder to me.

Lucien lived in a house in the hills above Sanary with his wife, LuLu, whose child, from an earlier marriage, Lucien adopted. She was his opposite — boisterous, always in motion and sometimes a scold. She had not been treated well in her previous marriage, and she worshipped Lucien who was very good to her. He was good to everyone.

Lucien was born and raised on the small island of La Galite, which is about forty miles off the coast of Tunisia and part of that country. When he lived there, in the 1940s and 1950s, it, and mainland Tunisia, were a French protectorate. Lucien often called this small island “a paradise.” Soon after Tunisia gained its independence from France in 1956, Lucien and his family left La Galite forever and settled, finally, in Sanary-sur-Mer. He continued his life as a fisherman there.

The stories and feelings of those who were born in the French protectorates and colonies and left after independence are fraught, and that is something we rarely discussed. I was not French, had not had that experience, so felt I was better off being silent. What I saw and knew was a fine man with a generous heart.

He would often invite me to his home in the hills for lunch on Sunday, a meal that extended well into the evening. Lucien was the cook for these meals, and a marvelous one he was. His specialty was bouillabaisse. Of course, the fish that went into the dish was what he’d caught himself.

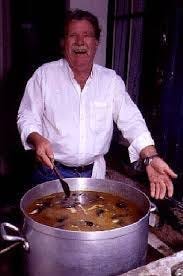

He had a deep, growl-y voice and a short, two-beat laugh. He had a dragoon-like mustache and curly brown hair. Away from the Irène, he always wore a crisp white shirt and jeans. He was always in a good mood.

Every June, he and some of his fellow fishermen arranged what was a true extravaganza — creating the world’s largest bouillabaisse. It was made in a vast iron cauldron, cooked in the town parking lot on an enormous wood pyre and fed 1500 people. It was a sight to see.

It was his kindness and good humor that I remember the most. He opened his heart and home to everyone, even to men who complained about the way he led the fishermen’s collective. They were invited to his long Sunday lunches, too, and were treated to his unbounded hospitality.

At one point, he said to me “Richard, quand tu auras fini ton livre, tu m’en enverras un exemplaire?” Richard, when you’ve finished your book, will you send me a copy?

“Oui, bien sûr,” I said. Yes, of course.

But that book was never to be. The publisher didn’t want what I’d written. So, this writing, here and now, will have to do, Lucien.

I see him in my mind’s eye, seated outside on the porch of his home above Sanary. There are seven or eight of us at his table. The day is calm and sun-filled. I can see the Mediterranean from where I sit, far below. Lucien is pouring more wine into my glass, urging me to take another helping of his splendid bouillabaisse, always accompanied by his creamy, crimson rouille and crisp baguettes. Lulu is walking about, exchanging quips with some of the other fishermen gathered there. There is much laughter, good food, good talk, and the day goes on and on and on. Lucien is presiding and urging everyone not to leave, even as the sun sets and it grows dark, to stay longer and longer.

And we all do.

A very fine tribute.

Another wonderful eulogy.