Frida

I went to an exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago a few days ago titled, “Frida Kahlo’s Month in Paris: A Friendship with Mary Reynolds.” Mary Reynolds was an American fine arts bookbinder who lived in Paris in the 1930s who had many friends in the Surrealist movement. Her lover was Marcel Duchamp. Kahlo went to Paris in 1939 at the behest of André Breton. He wanted to include some of her paintings in an exhibition. While in Paris, Kahlo developed a kidney infection, and Mary Reynolds offered her apartment for Kahlo to recuperate. Thus her month in Paris.

It seemed to me an exhibition with a slim premise. If the size of the crowd was any indication, I could well be wrong about that. It doesn’t matter, because the exhibition allowed me to get a good look at some of Kahlo’s paintings, always an inspiration.

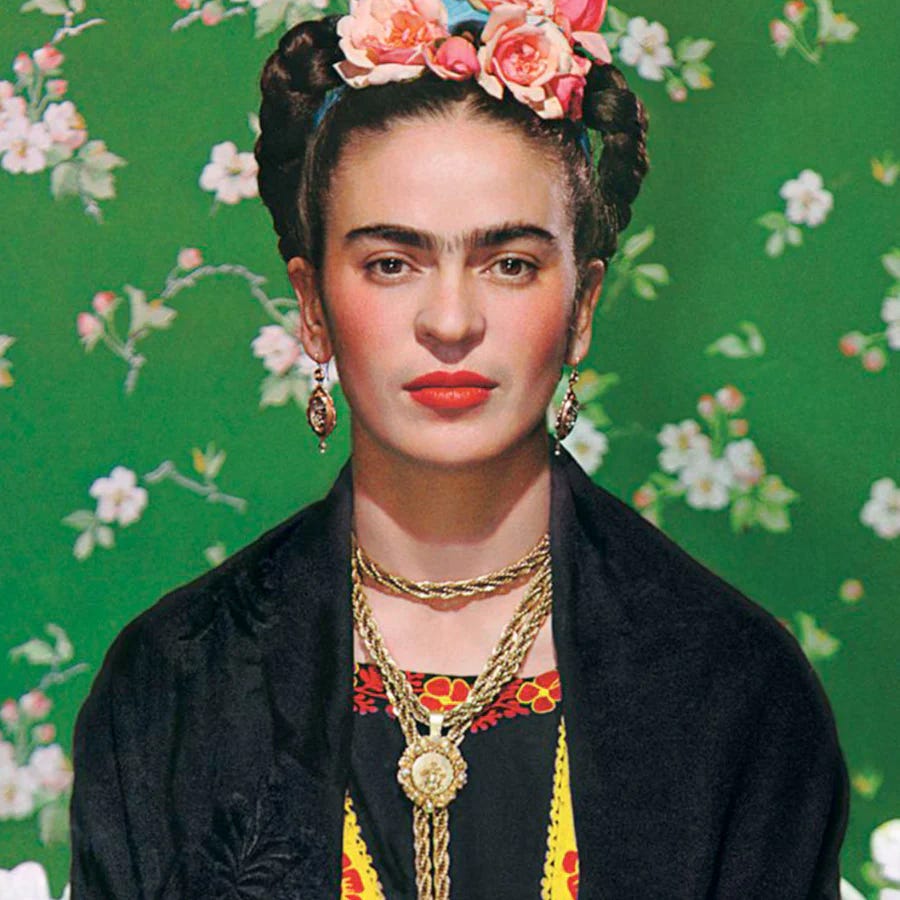

Fifty years ago, Frida Kahlo (1907-1954) was not well known. That has radically changed. She’s on T-shirts now, a movie has been made of her life, and when you say “Frida,” people know who you mean. Her face, with that dark unibrow, intense gaze and flowered hair has become as iconic as Picasso’s visage. If you want to know more, I might start at this website, where you can get a good overall idea of her life and work, including a sample of her remarkable diaries.

Many of her paintings are self-portraits, often dramatic and surreal—at times bloody and nightmarish. Has any artist been as fiercely, uncompromisingly truthful about themselves as she? When I look at a Frida Kahlo painting, especially a self-portrait, I am awed by how brave she was in her life and in her art. She stands, or sits, naked before you, not literally (though sometimes) but in a more daring way: her soul is naked.

Her life was full of pain, both extreme physical pain from a terrible bus accident when she was 18 that nearly killed her, and emotional pain from her labyrinthian relationship with her (twice) husband, the famed Mexican muralist, Diego Rivera. I would think now that many more people know about her, and her work, than about Diego Rivera’s, an artist who overshadowed her in her lifetime.

She often wore vivid Tehuana dresses, from an indigenous culture in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. When she was away from Mexico, she was sad, she yearned to return.

There aren’t that many Kahlo paintings in the exhibit. Still, they’re striking, pulsing with her bravery and skill. There is something that a painting can give your mind and heart, not to mention your eye, that no other art form can. There is a directness that paint—or whatever medium the artist uses—provides that your eyes drink. The painting doesn’t move, it doesn’t speak, it doesn’t make a melody. But it has a forthrightness that you absorb like a plant absorbs water.

Kahlo always gives you the truth, often in brutal images where she is suffering pain, where she can even be bloodied. If you want to see her at her most unflinching, look at her 1932 painting, Henry Ford Hospital, which depicts her miscarriage with a stark sense of loneliness and sorrow. It isn’t just the shocking imagery that she gives you. It’s all of her, every single secret, every flaw, every disappointment, every yearning. Her paintings can be hard to see.

She also dispels any declaration that you can’t make yourself the overriding subject of your art with any lasting value. She did. She painted fifty-five self-portraits. Her work embodies Ezra Pound’s definition of literature, which I will broaden, “Art is news that stays news.” Kahlo’s work, which is to a great extent about her, is ever new.

The words at the top of the painting above from the exhibition, “Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair,” are taken from a popular song and are translated as, “Look, if I loved you it was because of your hair. Now that you are without hair, I don’t love you anymore.” She painted this self-portrait in the wake of her divorce from Diego Rivera. It was painted eighty-five years ago but could be painted tomorrow.

Rivera was not faithful. Kahlo wasn’t either. But Rivera’s infidelities were more frequent and in at least one case, cruel. He had an affair with Kahlo’s younger sister, who Kahlo adored. Kahlo said this about Diego Rivera, “I cannot speak of Diego as my husband because that term, when applied to him, is an absurdity. He never has been, nor will he ever be, anybody’s husband.”

After seeing the exhibition, I went to the Chicago Public Library to learn more about Kahlo. I found a book titled, Frida Kahlo: Face to Face, by the artist, Judy Chicago. It gave me a chance to see many of Kahlo’s works in a single volume. Chicago’s offhandedness about Kahlo’s work, which sometimes borders on the dismissive, didn’t sit well with me. But looking at so many of Kahlo’s paintings was wonderful.

If you are looking for someone who never averted her eyes, who spoke the truth always with paint and with words, look to Frida Kahlo.

Thank you Rich 💜

Beautiful literary portrait of an extraordinary woman Just today I wrote a thank you note on stationary bought at the Nelson Adkins museum after visiting for a Kahlo/Rivera exhibit. For some reason she captured my soul!