On a bright September day in 1972, I walked up to an apartment building at 8 Duke Street in London. I looked at the list of names next to the door. I found who I was looking for. Nervously, I pressed the buzzer next to the name. Pause. Then I heard, through the intercom, a nasalized, even-keyed voice.

"Yesss?"

"Uh, it's...Richard...Goodman. From America."

"Come on up."

Buzzzz. Door released.

I walked three flights up, and, arriving at the door, I knocked.

It was opened by William Burroughs.

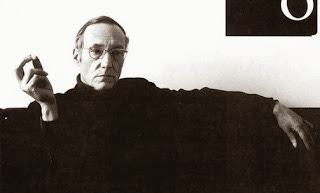

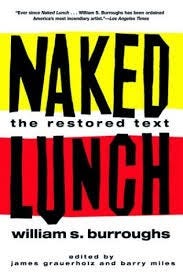

William S. Burroughs himself. The author of Naked Lunch, The Yage Letters and Junky. This was the same William Burroughs who had been called the father of the Beat Generation, the friend and mentor of Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg. There he was, smaller than I had imagined from the photographs, wearing a dark turtleneck, gray hair pulled over to cover some baldness. He beckoned me in.

I had written my Master's essay on Burroughs, and, during the process, had written him in care of his publisher with some questions. He replied! We struck up an irregular correspondence. When I wrote him I was coming to England and asked if I might come see him, he said yes.

That is how it came to pass that I was in William Burroughs' London apartment. At first, he seemed shy, even a bit awkward. He sat on a stool in the center of his small living room with a cigarette almost always pressed to his lips or dangling from his hand. Ashtrays seemed to grow hills of butts quickly, and soon the room was very smoky. What was I going to ask him? There were so many questions. Thankfully, he began.

"I just got back from New York," he said. "I flew over there with the film script of Naked Lunch. Terry Southern and I were working on it. A producer said he was interested. I think he does ‘The Dating Game’ or some quiz show. So, Terry and I flew out to LA at his expense. When we arrived, this big black shiny Rolls-Royce met us at the airport, whisked us on into town. Well, it turned out he wasn’t interested. He said we’d have to cut out all the sex scenes and a lot of the scenes with violence. But what’s Naked Lunch without sex and violence?"

He spread his arms to indicate "nothing."

"Terry and I did some cutting, but he still wasn’t satisfied, so we gave it up. When we went to leave, the Rolls had shrunk considerably, down to some kind of mini. I said to Terry, 'We’d better get out of here fast before he decides not to pay the hotel bill.'"

He talked more and, gradually, he loosened up. I'm not sure I ever did. It all seemed so unbelievable to me. I was just twenty-seven. This was helped by the fact that friends of his began showing up all through the day.

I told him that I liked The Yage Letters very much (a book consisting of an exchange of letters between Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg) but that I didn’t like Allen Ginsberg’s contribution. I thought it was self-indulgent. (God, that sounds insufferable now.)

"Oh, well," he said. "Allen has this idea that the whole world is love. Everyone is everyone’s brother, that kind of thing. He’s always felt that way. But I have a different view. I think there are sinister people about, trying to do you harm."

What about the revolver the character Lee (an early pseudonym for Burroughs himself) carried in Junky? Did Burroughs himself ever carry a gun? I was not going to ask him directly about his shooting his wife dead during a William Tell game gone wrong when he was living in Mexico in the early 1950s.

"Ohhh, yeah. When I was in Mexico City. I used to have this big ol’ .380 automatic. Used to stick it in my pants, right here." He pointed to his stomach-belt area. He was getting into character. "I remember one day I went into this pissoir, and I was waiting for my turn, when this man comes in — a typical punk — and he pushes his way in front of me. So, I opened my coat and tapped the handle." Pause. "He didn’t go into that pissoir ahead of me."

At a certain point, everyone decided to go to a restaurant in Soho. A caravan formed, and we headed out. It was, ironically, a Mexican restaurant. We ate and drank a lot. I'm not sure why now, but I asked him about Norman Mailer.

"I like Norman,” he said slowly and precisely, "A lot of people say they have trouble with Norman, but I don’t. Get along with him quite well."

He seemed distant, so I let him be. Afterwards, we all walked out into the London night. Burroughs seemed a bit wobbly to me, and I was worried that he might have trouble finding his way back to his apartment building. He was going to walk. He was in a bright mood now. He shook my hand warmly.

"Ok, baby," he said. "You’ve got my address. Next time you’re in London, look me up."

He waved and ambled off down the street. We all watched him disappear into the blackness of the night. Then we turned away and began walking.

"Will he be all right?" I asked one of his friends.

"William? Oh, sure. Somehow he always seems to find his way home."