I went to see the exhibition, “Van Gogh’s Cypresses” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York the other day.

It’s not a huge show, but it’s substantial enough. I’m not sure exactly how many paintings and drawings there are, but I would estimate about forty. Unlike the Impressionists room on the second floor of the Met where the lighting is strong, clear and bright, the lighting here, on the first floor, off the section where the Greek vases are displayed, in a room I’ve never even seen before, is muted, soft, quiet.

Most of these were painted by Van Gogh when, troubled and depressed, he was at the hospital in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, in the South of France, where cypress trees flourish.

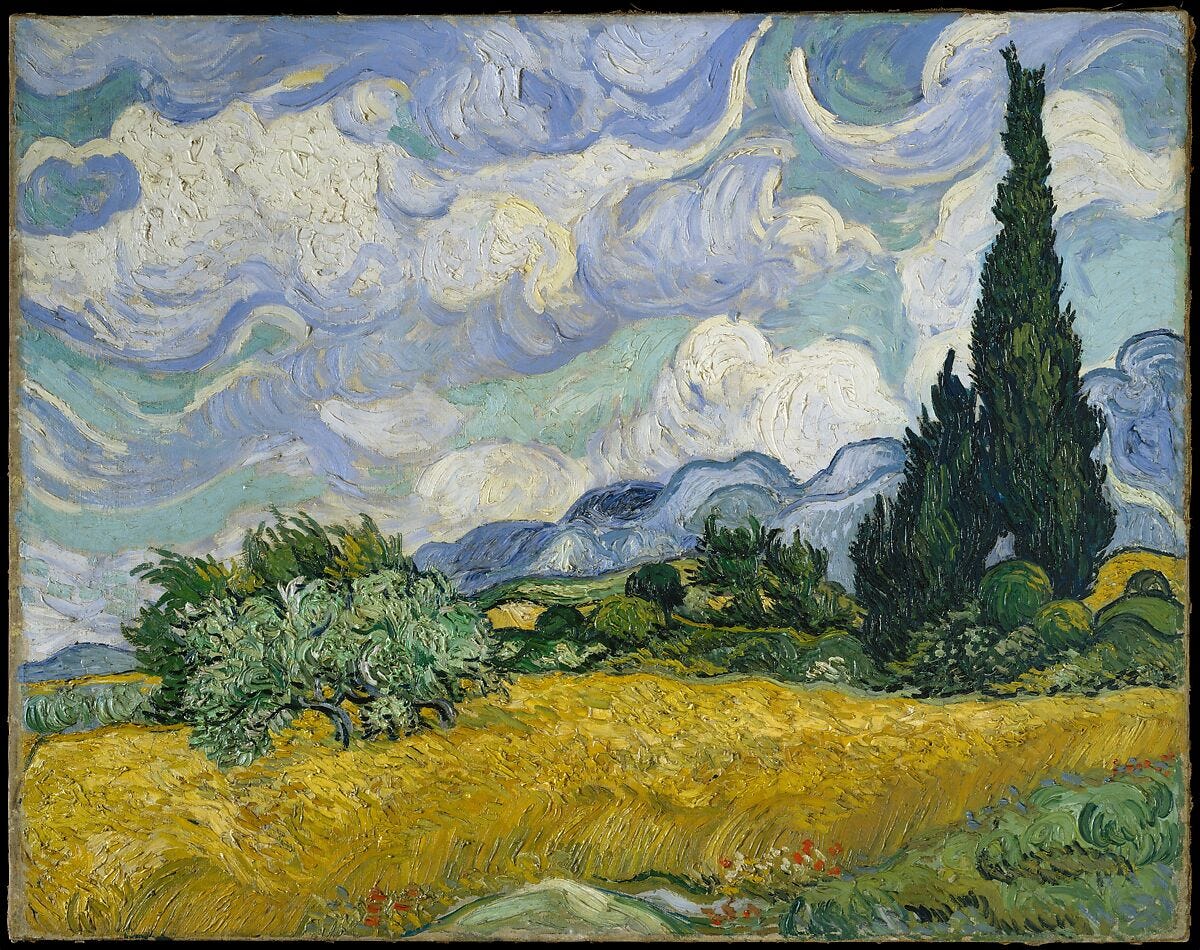

I am, as I would guess many of us are, familiar with some of Van Gogh’s paintings of cypresses. I’d seen two of them at the Met many times. One, Wheat Field with Cypresses, I like very much. It looks to me like a daytime version of the famous The Starry Night. Look at that swirling sky.

What I didn’t realize, and probably should have if I’d thought about it at all, is that in order to be chosen for the exhibition, a painting didn’t have to have cypresses towering, front and center, as in the painting above, but anywhere in the painting. It didn’t matter where and how many.

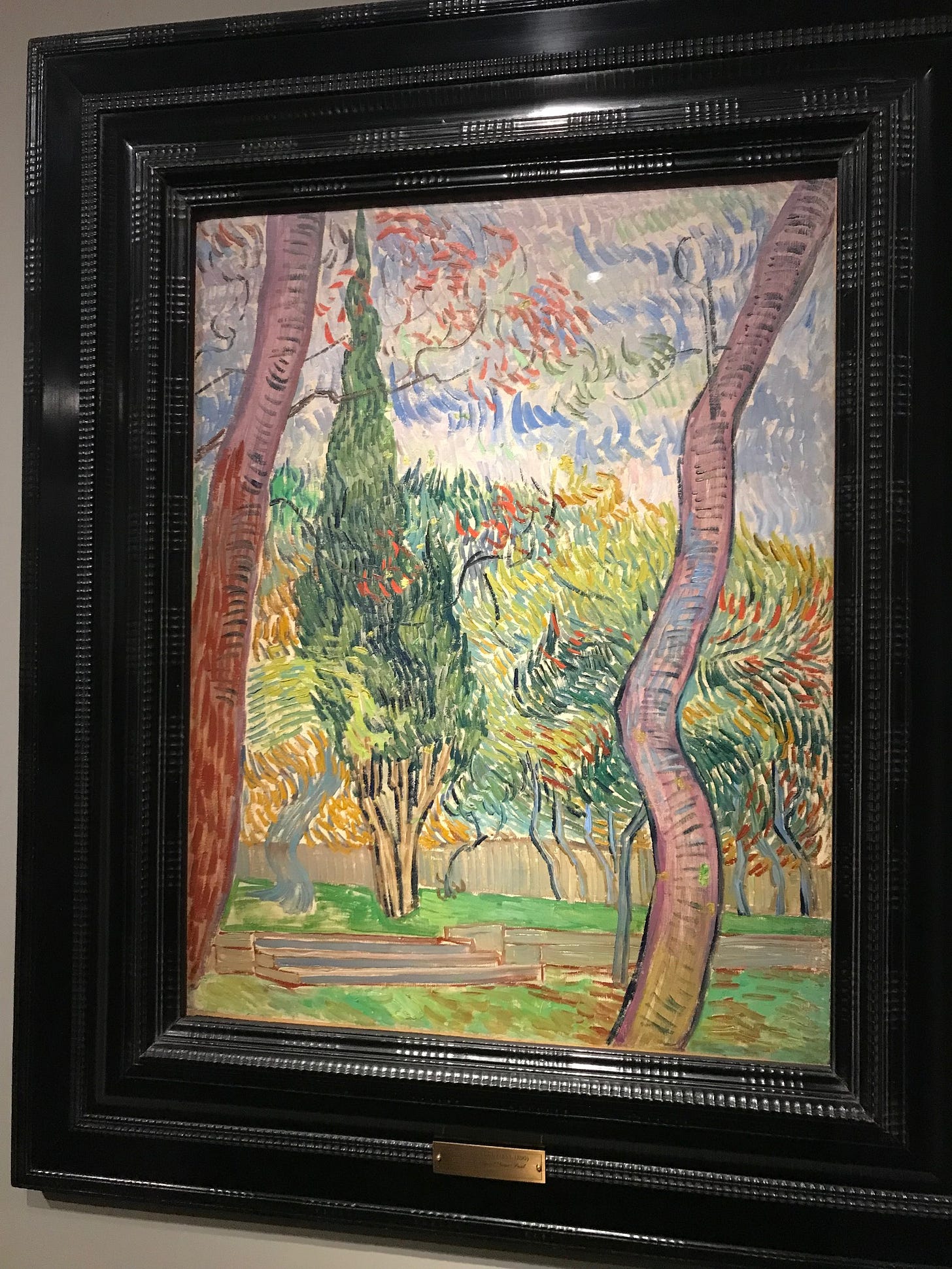

That expands the range considerably. This is taken to a clever extreme in the painting Window in the Studio where the cypresses are in the form of Van Gogh’s own paintings hanging on the wall, very lightly rendered. The top one is Trees in the Garden of the Asylum. (You can see it further below.) There is also a dab of cypresses seen through the window.

What this means is that the show is, despite the singular emphasis, very diverse. At least half the paintings I had never seen before and did not even know they existed. Not that I would be expected to. Overall, you can’t but be impressed by Van Gogh’s artistry, of course, but also by his fiery curiosity and his relentless determination. Flagging writers like me will have a hard time coming up with excuses for not working after going to this exhibition. Mental struggles and lack of money never stopped Van Gogh.

So many people adore, worship Van Gogh, that there will never be a need to attract new viewers to his work because he is underappreciated. Exhibitions of his work are a welcome preaching to the choir. I am a member of that vast choir. We all have our personal relationship with Van Gogh. I come to his work often for inspiration and advice.

In what other painter is passion and skill so unforgettably forged? Look at those swirling brushstrokes. Yes, you can see the brushstrokes in other artists’ paintings, and that is one of the great pleasures of looking at a painting, among the many. You feel the human hand. There it is, reaching across time. With Van Gogh, has paint ever been choreographed like this? With such exuberance and freedom? The paint is applied carousingly, seeming nearly out of control, yet there it is, before you, when you step back, the controlled masterpiece.

Some very familiar paintings are here, like The Starry Night, on loan from the Museum of Modern Art. That painting has crowds enveloping it, and can be difficult to see. Wait until the tide recedes. Meanwhile, there are so many other wonderful paintings. Many of them are dominated by color schemes I’d not encountered in Van Gogh before.

For example, there is Landscape from Saint-Rémy, cypresses diminutive behind a farmhouse in the distance, with its high-altitude landscape colors at the forefront, like something you’d see in the upper range of Wyoming or Colorado.

You can see the aforementioned Trees in the Garden of the Asylum, with its double-jointed tree to the right—along with cypresses, of course—that hangs from the artist’s wall in Window in the Studio.

There are some of his letters, too, because they have drawings of cypresses in them and/or speak about Van Gogh’s struggle to capture cypresses on canvas the way he thought they should be rendered. The one below, right, is to his sister. (Van Gogh wrote most of his letters in French.) His handwriting is precise, orderly, calm. Unlike the paintings.

And there are drawings by Van Gogh. It’s always interesting to see the searching mind.

Many of these photos are mine. I usually take smug satisfaction in not taking photographs at an exhibition with my phone. I look down on the unclean masses taking shot after shot—and who, as I imagine, are not looking at the paintings at all. But I do look! I want the actual experience, not a souvenir! I want to be engaged with the painting!

Well, so much for smug satisfaction. Funny what you learn in a museum.

What can you say about Van Gogh? Really?

Just this. At one point, I looked around at all the people and had one of those moments I sometimes have in museums where you have lots of people, all kinds, gathered in rooms to see an artist’s work. And that is: how much Van Gogh gave to the world. I don’t want to get all Don McClean on you here, but he has been dead 133 years this month, and he is still very much with us. The work is still fresh, challenging, inspiring, moving and beautiful. People gaze at The Starry Night today—or any number of Van Gogh’s paintings—and are astonished, awed and grateful. And they always will be. If he only knew.

Just a gorgeous tribute, Richard. I wonder, I've always wondered, if Van Gogh's fascination with cypresses, apart from their intriguing humanoid shapes, might have to do with the fact that in the Mediterranean they are the traditional trees of cemeteries, lining the allées leading to the holy ground and often shading the graves with their dark masses. Or am I giving way to a fervid imagination?

A wonderful story painted with words and tinted with admiration! Thank you, Richard, for taking me with you to the Met. What a great way to start a new day and no “excuses for not working after going to this exhibition.” I’ll draw “relentless determination” from the artist and will call today My day with Van Gogh