He came to Virginia Beach with my Aunt Elsa and their two kids every summer and stayed with us a few weeks. They were from New York, and they brought New York with them. As a kid in 1950s southeastern Virginia, I only knew the way my family and friends spoke. Uncle Howard and his kids said words in ways that made my brother and I laugh and demand, “Say that again!” They spoke fluent New York-ese. Of course, from a boy’s narrow perspective, they were the odd-speaking ones. Not us, with our twangy Virginia accents! I was always happy to see him and his family, especially my Aunt Elsa, my father’s younger sister. I adored her.

Howard was bald, glassy-headed bald, with the semicircle border of hair that always makes bald men look even balder. As a kid, I’d never seen a bald man before. Or certainly not one up so close. Baldness seemed a bit scary to me. It was disturbing. Why was he bald? Had he done something wrong? His voice was loud, nearly auditorium-loud. He was genial, though somewhat distant.

Howard was by profession a classical music producer. He worked for years for Columbia Records, one of the most prestigious labels in all classical music then. He knew, and had recorded, many of the great classical artists of the day, including Isaac Stern, George Szell and Mstislav Rostropovich. Names, when I was a boy in 1950s small-town Virginia, I had no sense of. It was only later, when I was an adult, that I realized the significance of his work.

But one artist he worked with was more significant to him than any other.

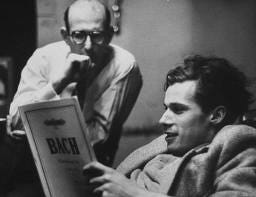

In 1955, a slim, pale, twenty-two year-old Canadian pianist walked into the Columbia Records studio in New York City to record some Bach variations. My Uncle Howard was going to be the producer of this record. The pianist was Glenn Gould. The record that emerged from the six days spent in the studio in mid-June was The Goldberg Variations. It was a record that upended the classical music world. It’s very difficult today to convey the impact this record had, particularly in 1950s America. Yes, there are household names in the classical music world today. Yo Yo Ma comes to mind. But no one that I know off has astonished and awakened the classical listening world like Glenn Gould did with his first LP.

I don’t remember when I first started to listen to Howard’s stories about that mythical recording session and the quirky perfectionist, Glenn Gould. Probably after I was in college and learned a little something about music. Howard was amused and fascinated by Gould, and indulged his eccentricities. Gould sat extremely low at the piano, for example. If the chair wasn’t low enough to suit him, he had the legs cut down to size. He hummed while he played—loudly. You can hear him on the record. There’s nothing technology could ever do to remove that. My uncle once gave him a gas mask to wear as a gag to muffle the humming. Gould played Back at Mach 3 speed, the notes emerging with the rapidity of a bag of marbles emptied onto a table.

Some musicians found Glenn Gould’s interpretations of music not only singular but exasperating. Still, there was so much wonder in his playing, he earned their respect. The great conductor George Szell said of Gould, “That nut’s a genius.” I know that Howard was proud of being part of Glenn Gould’s momentous recording debut, as well he should have been. In turn, I was proud that Howard was my uncle. Sometimes, for pure effect, I’d bring it up, say, at a party. “You know Glenn Gould’s Goldberg Variations? Well, my Uncle Howard produced that record.” From those who knew the record, I got what I was looking for: wide eyes, a step backward and, “Really?”

As a young man about to try to have a go at it as a writer, I was intimately aware, for the first time in my life, of what a living artist could do. He could walk into a studio and change the way people thought about music. Or at least about a composer. And people did think about Bach differently after Glenn Gould’s recording of The Goldberg Variations. In the 1950s in America, artists were not role models, believe me. But when my uncle spun his stories, and when I listened to the record and to the peregrine falcon flight of Gould’s hands across the keys, I felt what one single person could do with, as Stephen Sondheim (a fan of Gould’s) put it, “skill in the service of passion.” That he was slightly strange (“He showed up in the studio on a broiling hot summer day in an overcoat and gloves,” Howard said to me once, laughing) made it all the more appealing.

Howard was the classic New York executive from the 1950s. When I was living in New York as a young man, he would take me to lunch from time to time. It was always in some restaurant in that executive-ridden area of midtown Manhattan. There, at least up until the 1970s, men would pour out of their office buildings at midday and flow into the many restaurants that catered to them. Much drinking occurred at lunch. Howard always had at least two drinks, Scotch on the rocks. He was of his time, and he wasn’t alone, by any means. I always felt here was something slightly forced about his drinking at lunch. Or maybe he just had to show that he was part of that hardy group of men who could down them at lunch and go back and conquer the world.

Having lunch with Howard was like stepping into a John Cheever story. This was an era—coming to an end, but still alive then—in which train times ruled lives. When you caught the 5:18 from Grand Central to, say, Armonk, where Howard and Elsa lived. Your world during the day was Manhattan, but the rest of the time it was in a bucolic town out of a movie with everything to scale, where you could find parking easily and where there were many families like yours. Howard didn’t like New York. I did. I swooned over it. He couldn’t understand that.

Uncle Howard was the first adult I met who had heroes, like a kid does. They were musical, of course—Isaac Stern, his beloved Glenn Gould, Rudolph Serkin, George Szell and Leon Fleisher, to name some. He knew them, he worked with them, he recorded them, he was in awe of them. He spoke of them with that slow-cadenced reverence you reserve for people you truly esteem. This sense of awe he had for these artists made me realize that even as an adult you could look up to someone, your eyes upward in wonder. I still have heroes, and I always will. I know this is partly due to Howard. And having heroes is, I think, one of the first steps toward trying to make yourself one.

This is the first time I've heard you mention Uncle Howard, and this is a wonderful tribute to him, Gould, and the power and appeal of Art Heroes.