It’s surprising to find yourself, or something you’ve written, as a source for part of a famous dead poet’s biography. Especially a famous dead poet with an exotic, volcanic life. I’m speaking of the French poet, Arthur Rimbaud (1854-1891).

I wrote an essay for a magazine about Rimbaud’s time late in his short life as a coffee trader in Ethiopia, about how he got there, unlikely as that was. I was thinking about writing something else about Rimbaud recently, so I promptly went to everyone’s convenient source of choice, Wikipedia. Lo and behold, there it is, citation number 72, a reference to the article I’d written twenty-three years ago and nearly forgotten.

It made me think of how strange it is the places we end up in our lives. Here was this enfant terrible, terrible child, possessed of extraordinary poetic powers, who ended up in Harar, in what is now northern Ethiopia, having abandoned poetry forever some fifteen years earlier, counting his money, forever concerned that local merchants were cheating him out of a few pennies, or whatever currency they used.

That’s not the way it began.

He sprang full blown as a poet from a small city in northern France, Charleville.

Sidebar: Patti Smith, an ardent lover of Rimbaud, made a pilgrimage to Charleville that she writes about in her lovely book, Just Kids. In a video, she describes, in her typical heartfelt, sweet, brilliant way, how she discovered Rimbaud as a teenager. A year ago, she had what she called “Rimbaud Month” on her Substack newsletter with more enlightening videos. I recommend watching at least some of them. No one I know of has talked or written about Rimbaud more knowledgeably and sensitively. Hers has been a genuine lifelong love affair. She even bought Rimbaud’s reconstructed home in France.

Arthur Rimbaud was writing lasting poems by the age of sixteen. He was a poet whose life was like one of those Roman candles that goes astray and sweeps erratically across the sky with the possibility of crashing into a house or a person or you. Everything about his life was dramatic, self-destructive and extreme.

He wrote incendiary, sometimes gorgeous, sometimes fearlessly sexual, sometimes frustratingly complex, and, at times, incomprehensible poetry in the remarkably brief period he wrote poetry. Which is to say, from the age of sixteen to about the age of twenty. His most famous poems are “The Drunken Boat” and “A Season in Hell.” I prefer poems like his early, exquisite, “Au Cabaret-Vert,” or “The Seekers of Lice,” or his bold depiction of early sexuality, “Memories of the Simple-Minded Old Man.” He has a line in that poem that sticks, “For a father is disturbing.” Patti Smith particularly loves Rimbaud’s “Ophelia.”

Nothing had ever been seen like this in French poetry before, even from Baudelaire. Suddenly, Rimbaud stopped writing altogether. No one knows why. The rest of his life, he was a wanderer. He went in search of something he could never find, because it wasn’t there. (Can any of us identify with that kind of Sisyphean search? I can.) He looked for it in Paris, in Indonesia, in London, in Cyprus, in Yemen. And, finally, in Ethiopia.

One of his last efforts was “Illuminations,” forty-odd prose poems it seems he wrote mostly when he was in England. Some people claim they understand them. (Patti Smith delightfully advises not to worry about that. Just experience them. She says poetry is a “code.”) Read one, and see for yourself. If you comprehend it, please enlighten me.

Some artists love Rimbaud because his chaotic, fiery life gives them validation for their own self-generated chaos. And Rimbaud’s life was as chaotic as any self-destructive American artist’s has been, if not more so. Typical is the affair he had with the (married) poet Paul Verlaine that ended with Verlaine, in a rage, shooting Rimbaud in the wrist.

As Allen Ginsberg said, “Rimbaud seems to be a complete turn-on catalyst to every poet in small town isolated, or big megapolis, staring at the city lights over the roof.” What that means to me is: don’t let those small-town minds stop you from becoming the comet that you are. So you destroy a few things, or lives, along the way. You’re an artist. Yes, an artist! A pass for crashing through life! But, really, Rimbaud harmed himself more than anyone else. Verlaine, after all, was responsible for his own life and marriage.

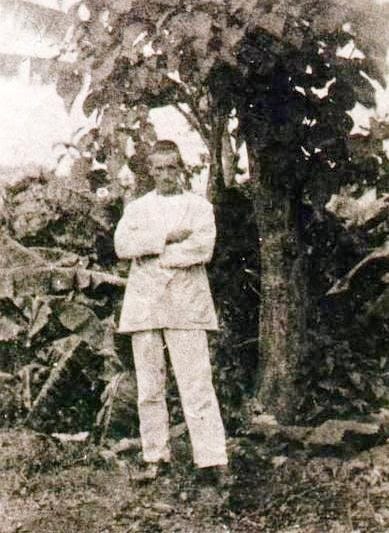

The last years of his life Rimbaud spent exporting coffee from Ethiopia—an astonishingly able linguist, he learned the two languages spoken there, Amharic and Harari, quickly—and smuggling guns. All he cared about was money. He took up photography. In those later years, someone realized who he was (Rimbaud had become famous in Paris without knowing it) and asked him about his poetry. “Disgusting!” Rimbaud replied. He had left that person behind long ago and, in the words of a biographer, had become “somebody else.”

One of his last letters, written to his sister from a hospital in Marseille where he was soon to die at the age of thirty-seven, says, “Our life is a misery, an endless misery. Why do we exist?”

The poetry remains.

Such an interesting read…intriguing the reader to want to explore further!👏