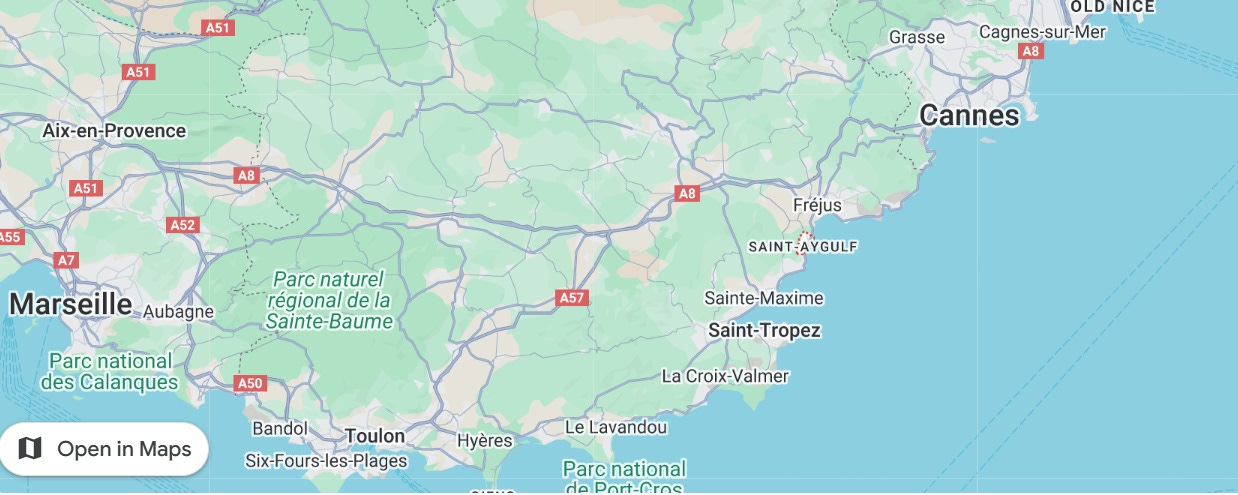

They said he was perhaps the last builder of pointus in France. He was 83 years old and lived in Saint-Aygulf, a small town on the Mediterranean almost midway between Cannes and Saint-Tropez. His name was Raphaël Autiéro.

The fishermen in Sanary, the coastal town about 100 miles west where I was living and researching a book, knew about him. It’s even possible they owned one of his boats at one time, but I could never verify this. I was told that he was in the middle of building a pointu for a contest, of all things. A well-known maritime and boat magazine was sponsoring a contest, “to reconstruct or restore the historical and traditional boats of the French ports.” The contest was divided into categories according to length and type of boat, and the judging would take place in Brittany in the summer.

I came to see him for the first time on the 19th of March, the day set aside by the church for St. Joseph, patron saint of carpenters. He lived in an old villa near the sea with his daughter, son-in-law and their children. I’d called ahead and asked his daughter if I might visit. Next to his villa was his large workshop. I knocked on the workshop door at 9:30 A.M. on a sun-filled morning. I heard that confident, raspy voice for the first time asking me in.

When I opened the door, I saw the pointu he was working on, huge-looking in its confinement, tilted to one side by wood supports. Sawdust and wood shavings were everywhere. Beautiful wood was leaning against walls and stacked in precise piles on the floor and jutting out from bins above our head. The aroma of wood filled the room. Wood, wood, wood. Motes of woody dust floated on sunbeams. The light shone through windows onto the many tools he had on a long work table nearby.

He stood there in baggy trousers and a T-shirt; he had a mallet in his hand. He was short, white-haired and powerful-looking. While we talked, he never stopped working. It was his eyes I noticed first. Raphaël Autiéro’s eyes were blue and limpid as the Mediterranean. They were strong eyes, full of hope, full of tomorrow, and they trained upon you with no glasses in the way. I looked as often as I could into his eyes—absolutely without clouds they were—and was astonished by their youth.

If a voice might be described, like a fine Bordeaux—earthy, powerful, perfumed with soil and vines and a whiff of the sea—this was Raphaël’s voice. It wasn’t the whispering, listless voice I heard emitting from the retraitées, the retirees, in Sanary. Raphaël’s voice came directly from somewhere vital. Though he had a wonderful smile, he also had great Italianate swings of emotion, and so I often heard him use this voice to full force. He hated the French government, and I can still hear him railing at them, “Des brigands! Des brigands!” Robbers! Robbers! His magnificent rasp carried to the far end of his workshop.

“So, you’ve come from America to meet an old boat builder?” he said.

“Yes, I guess you’re famous all over the world,” I said. I wasn’t far off. Through the small world of enthusiasts, he was even known by a few boat builders in America. He’d had visitors from all over France and beyond.

“Well, what do you want to know?” he asked. He began to work as we talked. He took up the mallet and began knocking. I circled slowly around his still skeletal pointu, its fresh, young ribs sticking out.

He began building boats with his father when he was twelve. He reckoned he had built about one hundred boats in his lifetime. Were they still in use? What was it like, I wanted to know, to be perhaps the last pointu builder in France. What about his sons? His grandsons? Weren’t they interested in learning?

“No. It’s hard for me to get them away from their television sets and their computers even to go on a short boat ride with me. I have to force them. When I do, they love it. But this,” he waved his hand at the boat, “this stays with me.” Raphaël was calmly realistic about how the world of fishing had changed. He wasn’t bitter. But one word about the French government, and he was off:

“Thieves! The government are thieves! I stopped building boats four years ago, because of their taxes! I had to pay more than I make.”

All I had to do was say, “L’ètat,” the state, and his voice would explode. These two boats he was making for the contest were an exception and would in fact be the very last he would make. The town of Saint-Aygulf was paying the cost but not all. Some of the money was coming from Raphaël’s own pocket.

“Why should we give him any special treatment?” a local tax official said when I asked him about Raphaël’s high taxes.

“But,” I said, “he’s a special case. He’s perhaps one of the last men who knows how to build a pointu—maybe even the last. He’s like a living museum. The taxes are high for him. Can’t the government make an exception?” The official was unmoved. “If he makes money, he will be taxed.” France, which has so often been tolerant of its artists, bending the rules in their favor—think Jean Genet—was rigid here. I just counted myself lucky I’d arrived at his workshop before Raphaël quit building altogether.

“Now the boats are made of Aleppo pine,” he said. “Before, we used mahogany from Gabon.” Look at the French words: L’acajou du Gabon, and suddenly the sense of France’s former colonies, that great adventure and exploitation, surges forth. You cannot help thinking of this country in days past—in days Raphaël knew intimately—with its rubber coming from Vietnam, cane sugar and rum from Martinique, leather and spices from Morocco, wood from Gabon.

“You must have good wood,” Raphaël said, stroking the unfinished boat tenderly. “The wood must be cut dans une bonne lune,” he said. During a good—or waning—moon. So, that the wood isn’t in flower, as he put it, and the sap isn’t rising. “When I find bad wood, I know it wasn’t cut during a good moon. It also should be cut in winter, in December or January, that’s best, so it doesn’t deteriorate.”

I stroked the smooth, nearly living wood, the grain and texture, and I let my hand glide across it.

“It feels so sensual,” I said, “like….” I bent forward. I was tempted to kiss it.

“Like the buttocks of a woman,” Raphaël said matter-of-factly.

“Yes!” I said, drawing back discreetly. I looked long at the boat he was building.

Raphaël looked moody. “Today, when I go to a woodcutter and ask him to cut my wood during a good moon, he says to me, ‘No, I can’t possibly guarantee that. I have to cut the wood when I can, when my men are in the forest.’ But I tell him, ‘I’ll give you one year to deliver if you can promise me that.’ But they still won’t.”

He had managed to obtain mahogany from Gabon for these boats, and so he was very pleased.

It takes him about three months to build a boat. If it is built well—by someone like Raphaël—a good pointu, well looked after, will last sixty years. It will more than pay back its original cost. A pointu is not an especially heavy boat. Of course, you can have different lengths, but the boat Raphaël was working on was 5.85 meters long (19 feet) by 2.20 meters wide (7 feet). It weighed just 900 kilograms, or about 2,000 pounds. Much less than the fishing boats in Sanary with their big diesel engines.

As Raphaël described it to me, the pointu has “the shape of half a nut.” It originated, it’s thought, in Naples, and probably its popularity spread north and west to France when fishermen found it well suited the erratic, short-spaced waves of the Mediterranean. It’s an open boat—like a rowboat in shape but worlds apart in spirit—it was, before motors, equipped with a lateen, or slanted, sail and up to four pairs of oars.

In their pointus, fishermen sailed—and rowed, if there was no wind—as far as Corsica, over 100 miles from shore. Mostly they stayed close to home, fishing a mile or two offshore. Men fished mostly for sardines, which were there in abundance. They also fished for scorpionfish, eel, wolfish and anything else they could net. For the most part, they went after la blé de la mer, as fishermen called sardines, the wheat of the sea.

“In the old days,” Raphaël said, “you had to have a light boat. In the winter, you might pull up your boat three or four times in one night. You’d leave at 5 PM, cast your net, come back around 9 PM, sleep for two or three hours and then go back out. Each time, you had to pull the boat up on shore. We didn’t have all these docks and anchorages back in those days. That’s why the pointu had to be light.”

Raphaël would often be asked to repair the boats he had built if, say, there had been an accident of some kind or if it needed fixing. He was often shocked by the condition of his boats. “Some,” he said spiritedly, “you could eat bouillabaisse off the bottom. Others....” He shook his head.

I saw him several more times after that first visit. Each time it was lovely to see how the boat had advanced. It was hard to finally leave the smell of wood, the sunlight streaming in, the motes dancing in the air, and the great, nearly finished pointu, leaning on its side. On my last visit I circled around the boat one final time, stroking it, letting my hand slide freely across its side. It was a room full of learning, skill and beauty. I thanked Raphaël for his time and for the privilege of watching him work. He was modest in reply, as always.

Soon after, I finished my time in Sanary. I’d been there for six months. It was time to leave. I left France and returned home.

Back in New York, six months later, I received a note from Raphaël’s daughter that said, “Papa died yesterday. Very, very sad.”

Here was a man who did exactly what he wanted to do with his life, and he did it well. He knew it. He had done what he was supposed to do on this earth. People had benefited from his gift, fed their families and made do. He had created beauty—a useful beauty. I hope I can say something like that at the close of my time here.

I was struck by the suggestion of logging wood when there is the least amount of light in the atmosphere. In Tuscany, when I was (re)building my old farmhouse, the workers insisted that the chestnut roof beams should be from wood harvested at the dark of the moon in January. If not, they said, you risk an infestation of woodworm and other undesirables. I like Raphaël's description of the wood "in flower." I imagine Odysseus made the same stipulation when he ordered the boats that would take him to Troy. And home again.

The story touched me because I watched those boats go out every morning and return in the evening from the balcony of my hotel in Cassis...not knowing the name of the boats nor the story behind the art of building them. They were the vehicle for the delivery of some fabulous loup de mer. I hope the art of when to harvest wood doesn't get lost in this world on a fast track.

That had to be a very special time for you.