It was a stone house that was big and old with many rooms and walls as thick as a fortress. We lived there for a year in a small village in a corner of Provence about an hour from Avignon. My Dutch girlfriend and I were escaping New York City—just had had enough. New York had beat us down, as it does, every so often, everyone who lives there. New York—we loved you but we needed to separate from you for a while. Where would we go?

To the South of France. Why not? We had the fortune to find a place outside of time. It was a lovely way to live, in a house that had been built 200 years ago, hewn out of stone found not in quarries but in the fields.

It wasn’t easy at first. The village life seemed as durable and unchanging as the house and as mute. It was a while before she and I could begin to fathom the rhythm of its ways. Why didn’t the villagers respond to our greetings, except for the briefest answers? Why weren’t they the least bit interested in us? Why didn’t they accept us with open arms?

A village in Provence can be exquisite and maddening. It took time for us to see that our sojourn was merely a blink in the villagers’ unwavering eyes. We did, at last, and it was the land that led us.

As she and I woke up day after day to a sun-flooded room, our casement windows open to the new morning, we began to become part of Provence. We couldn’t look out onto the softly undulating hills, with their legions of precisely-lined vine plants, without giving away our hearts. We couldn’t smell the subtle morning air, a perfume of everything that grew there, without becoming a little more lost in love with the place. We couldn’t have our vision enhanced by the marvel of the light without wanting never to leave.

The gap between their ways and ours lessened, and that was in part due to the power of the place. We were under its sway, and so many of the things that were important to the villagers became important to us.

We walked the rough little hills above the village and saw wild thyme growing. The plant is like a dwarf version of a stunted tundra tree, all twisted and leaning. It’s a tough thing, difficult to cut. I began using it in my cooking. I soon found the taste is not the same as domesticated thyme. Like many wild versions of a plant or spice we know, its flavor is more subtle and quieter and more interesting. It’s a good metaphor for some of the villagers we met. They were wild thyme. Their tastes weren’t revealed just by a single encounter.

No, we’d never be paysans—as the villagers unhesitatingly called themselves. Not farmers, peasants. They were people rooted to the land. Eventually, most everything in Provence comes back to the land. Pays, the root word of paysan, means “country.” If you visit Provence, try to walk in the maquis or the garrigue, the scrub hills, full of dry wonders and simplicity. Let yourself become part of this remarkable land. Day by day, we surrendered to its spirit.

In surrender, Provence simplified our lives. That’s what the place will do. Simplicity will come over anyone who stays there for even more than a few days. “Only in this sun-steeped country,” Colette writes, “can a heavy table, a wicker chair, an earthenware jar crowned with flowers, and a dish whose thick enameling has run over the edge, make a complete furnishing.”

We began to understand, like everyone else who has become attached to Provence, that there is no place on earth like it. No one can possibly prepare you for this consistently ethereal level of beauty. Not any book, movie, or essay. No painting. Not these words. Nowhere else do you find such a confluence of pellucid air, fierce sun, ravishing smells and tastes and grace.

It may not be your country, but it may not altogether foreign to you, either. As M.F.K. Fisher said of her first visit to Aix-en-Provence, “I was once more in my own place, an invader of what was already mine.” It may be singular, but you can become its citizen. You may feel as if you were born there, and perhaps you were.

We had a used car we had bought, scruffy and prone to seizures, but on the whole reliable. In it, we ventured near and far in the South of France and came to see much more of the land beyond our village during that year. We went to nearby Avignon first. What a shock it was to go from our little hamlet, with its stubbornly self-important ways, to a city that has had such a prominent role on the world stage. We—at least I—felt Avignon is a sad place. Even though it’s on the lyrical Rhône, that magnificent water, the city has a melancholy air. Cities have lived lives, too, and when you walk them, you begin to see exactly who they have become. I think of Avignon as not at peace with itself. For that very reason, it’s impossible to forget.

We went to St.-Rémy in search of van Gogh’s ghost and then walked the sun-scorched hills nearby, the Alpilles, which he painted. We drove to Marseilles, a city as unjustly feared as New York, and that’s a pity, because Marseille is so sharply flavored and so alive. M.F.K. Fisher described the Marseille she loved as “mysterious, unknowable,” and I think it will haunt you and draw you back as it did her. We went to Nîmes and walked into its massive amphitheater and felt dread and awe in the face of the Roman Empire. We drove to L’Isle-sur-la-Sorgue and watched trout swimming in the cool little stream and stayed in that pretty place until dusk at a table outdoors. We saw all these wonders and many more, and we continued to make forays into the heart of the heart of Provence all year.

But no matter how far we went, we always came home to our village. To the well-wrought house that now was our home. To the simplicity and timelessness of a life that unfolded before us. We met everyone in the place, and we began to piece together their lives. We were even luckier to get work in the fields, so we experienced Provence’s light and air and scents throughout the long days. They paid us, too, in francs, by God! The wine tasted better in our dirt-caked hands, and so did the daube I cooked for us when the day was through.

It was a privilege to go to sleep weary in our village and to wake up with that slight feeling of reluctance physical labor bestows on you every morning. We had the gift of responsibility in Provence, and how much luckier can two people get? You cannot steal idle moments when everything is given to you.

We were not used to the hard work, to the bending, pulling, digging and planting. We were old people for an hour every morning, but nothing in the world would have induced us to quit. We went home to lunch at midday as the villagers did. We spooned our soup and devoured our bread happily with the morning’s cool still hovering over us. Sundays became as precious to us as long-awaited vacations. Nothing that year was sweeter than buying villagers we liked a pastis with money we earned working their land. If you can work in Provence, even for a single day, you should do it. It will bind you closer to the place.

Despite the fact that we were frugal and that we worked, we could see our money dwindling. This alarmed us and saddened us. We didn’t want to leave. We wanted to stay forever.

But we had to leave. We had to return to New York City, to that city we no longer felt was our home and wondered if it could ever be again. (It could.) We had to say goodbye to Provence, and to the village we had grown to love and that had taken root in our souls.

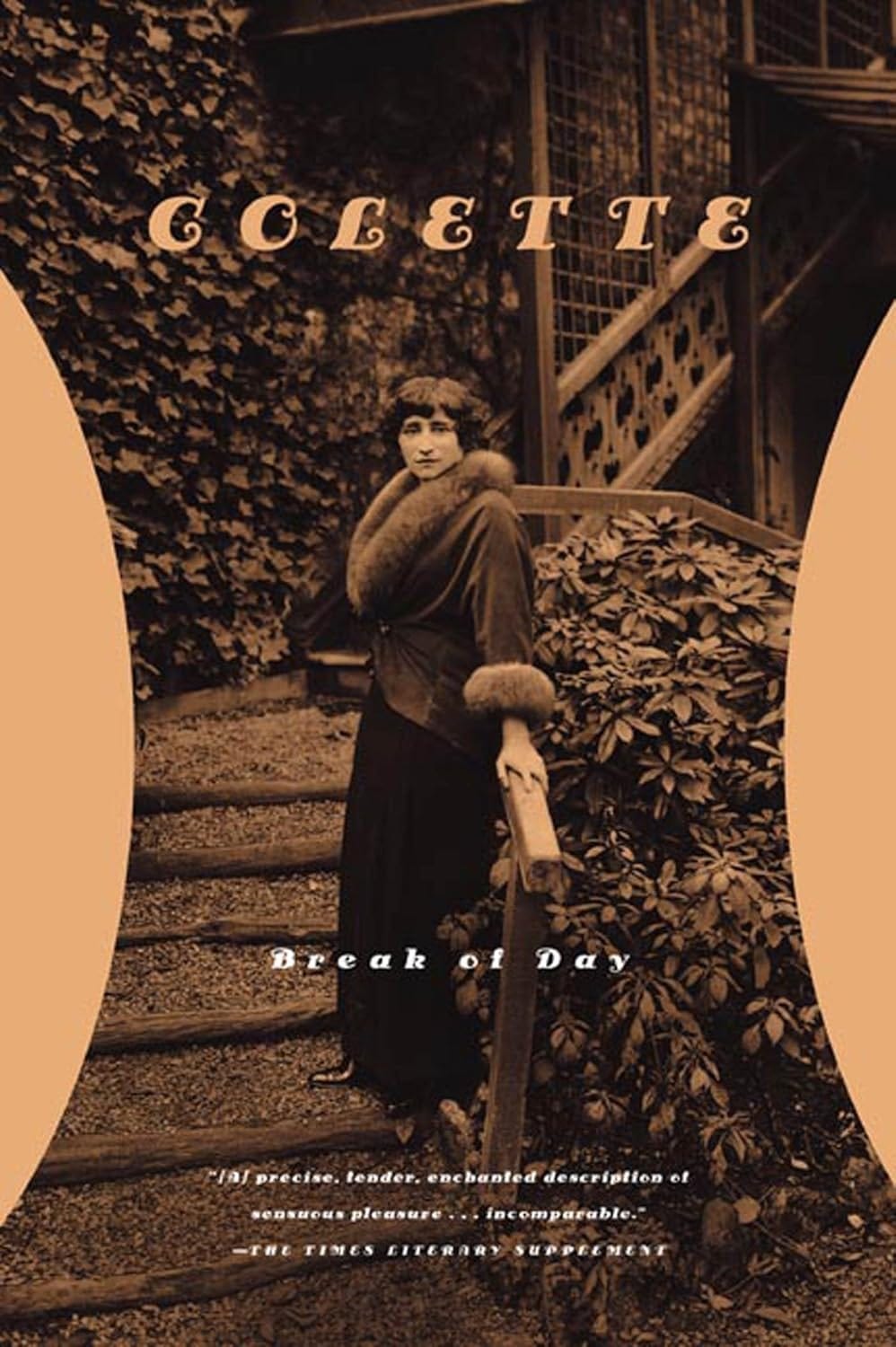

Colette’s words I quoted are from her book, Break of Day. If you love Provence, or you are going to Provence for the first time, I hope you read it. The prose is as potent and sensual as those Dionysian scents distilled from Provençal flowers in Grasse. Colette had a house in St.-Tropez, and she began staying there before that fishing village was anointed by Parisians to become the place to go to. Break of Day was published in 1928, but not an observation is obsolete. Her house was above the village, and she writes about gardening, the movements of the day, her animals, the people who come and go and the delicious, sensual tastes of the place. Here, Mother Nature doesn’t wear a silky dress; she walks naked. Colette writes with a pen dipped in sun, oil, sweat and salt.

“What a country!” she exclaims. “The invader endows it with villas and garages, with motorcars and dancehalls built to look like Mas. But during the course of the centuries how many ravishers have not fallen in love with such a captive? They arrive plotting to ruin her, stop suddenly and listen to her breathing in her sleep, and then, turning silent and respectful, they softly shut the gate in the fence. Submissive to your wishes, Provence…they have no other desire, Beauty, than to serve you and enjoy it.”

Go. Submit. Surrender.

Lovely to read and imagine being there, Richard. AH.

So much poetry and passion for Provence in this piece, Richard. I also enjoy seeing pictures of the village and its population.