Robert Finch, the esteemed nature writer, died September 30 on his beloved Cape Cod. He was 81.

I met Bob at Spalding University in Louisville, Kentucky, in 2005. We were paired to teach a creative nonfiction workshop as part of Spalding’s MFA in Writing program. We would teach many together. Thus began a nearly twenty-year friendship that I am mourning today and will continue to mourn for a very long time.

I want to provide some words about Bob, because he was a wonderful writer and wonderful friend, and the more people who know about his work, the better.

The expression “writer’s writer” is often used to describe certain kinds of writers. Usually that means their standards are pure and exacting and their sentences gems—clear, strong, lyrical and nearly impossible to improve. I would say that description fits Bob well. His peers—Annie Dillard, Bill Roorbach, Edward Hoagland, Barry Lopez and Marge Piercy to name a few—respected and admired his work, and they said so.

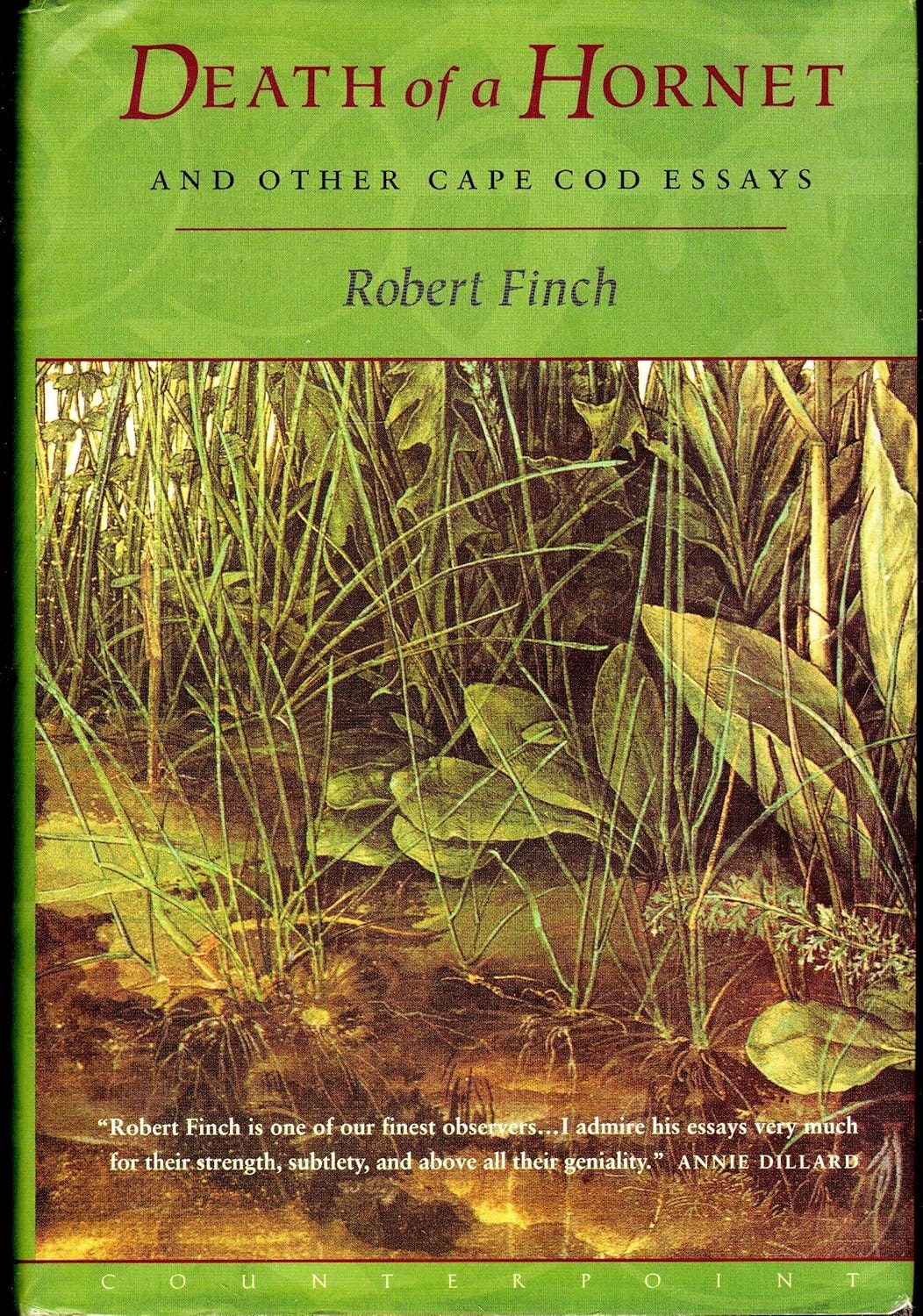

No eye looked more closely at what was right before him and no hand wrote more compellingly and revealingly about what that eye saw than his. I think of William Blake: “To see a World in a Grain of Sand / And a Heaven in a Wild Flower.” He saw that. All you need to do, for example, is read his marvelous essay, “Death of a Hornet,” from his collection of the same name, to see what I mean. He describes a hornet’s buzzing “like a yellow-and-black column of electricity slowly sizzling up the window pane.” It’s exciting and fulfilling to read his words.

Bob wrote about a hornet in his office or a spiderweb affixed to a boat and what, in a title of one of his radio pieces he called “a remarkable unremarkable event” and made that writing indelible with his keen eye and his surgeon-like prose. He saw in these intimacies large lessons to be learned. He was an appreciator of nature who never lost his sense of humility about nature, who never saw his own feelings and person as the larger subject.

Listen to almost any of his radio pieces his did for the local Cape Cod NPR station. For example, the aforementioned “Spiders on the Lake,” which was broadcast a year ago. It begins with a discovery of a spiderweb affixed to a boat and concludes with the possible fallibility of Darwin’s Origin of Species. How surely and genially—to use Annie Dillard’s description of his work—he led his readers. (Click here to find many more of his sharply-etched, highly entertaining radio essays.)

He wrote memorably about people he encountered as well. Look into The Iambics of Newfoundland. Read the first chapter about a hitchhiker Bob picked up and who gave the book its title. I’m smiling, having reread it just now.

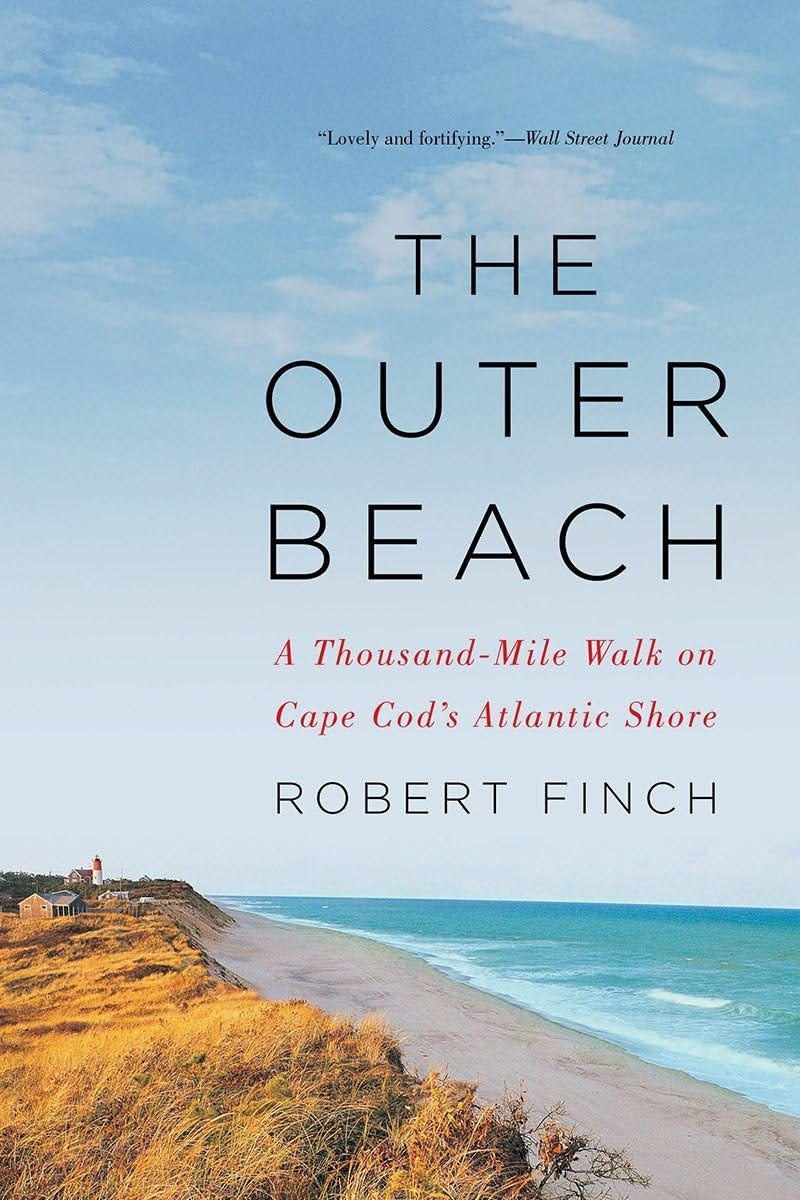

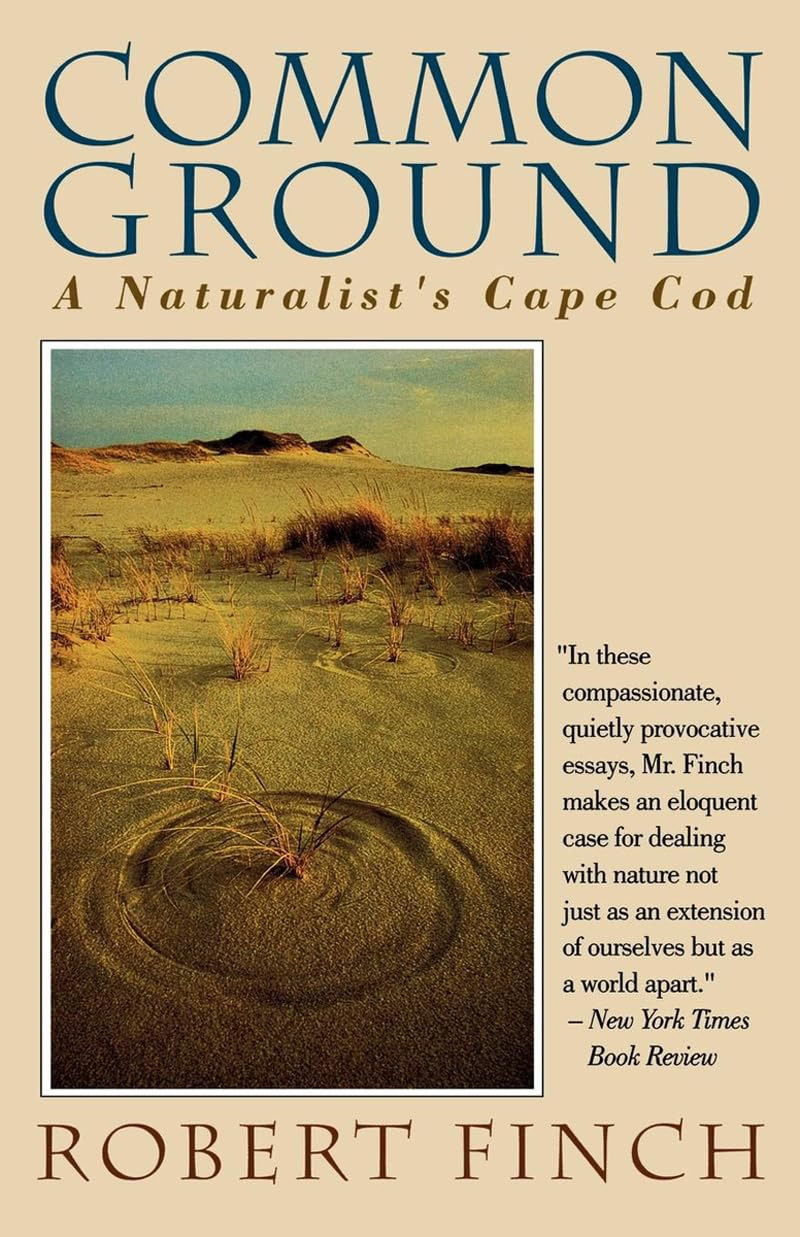

The settings of his books were mainly two: Cape Cod, by far the most prominent, and Newfoundland, where he had a house for a number of years. His last book, which will be published posthumously, concerns Newfoundland. But it was Cape Cod, a place he knew as well as any person ever did, that captured his attention enduringly and inspired him the most.

He did not, as so many American writers do and have done, spend his career teaching at a college or university. His writing was free from the baleful eye of academia, originated and was nurtured solely by his own passions and standards. Those standards were high. He was a most generous friend and person, a warm presence, and he had a delightful sense of humor. But when it came to writing, he never compromised.

I’d send him my work from time to time, and he usually liked it, but if he had something pointed to say about it, he did not hesitate. This is from a letter he wrote to me:

“I enjoyed this piece - I really did. But sometimes I wish you'd dig deeper. Not every time, but sometimes, regularly. I know you can - I've seen you do it. Being in a happy place, where you seem to be at this point, can make it harder, but as they say, "If writing were easy….

Your gadfly friend,

Bob.”

I can feel his strict gaze on these very words even now. I know some students at Spalding bristled at his rigor, but little did they know the privilege they had to be under that expert gaze. I hope they do know now.

I visited him at his home in Wellfleet on several occasions where he lived with his wife, Kathy, whom he adored. We would sit before his fireplace and discuss writing and books and writers. Because what was more interesting or important than that? He read widely and deeply. His curiosity was always famished. He urged me to read John O’Hara, for example, a writer popular in the 1940s and 1950s but who today is largely forgotten—especially The New York Stories. I got the book, read it, and saw that he was right, that O’Hara could indeed write, and we had many feasts on O’Hara’s work, sustaining me, at least, through one winter.

It was at Spalding where I was closest to Bob. We taught together, walked and talked together, and dined together, often with our friend Phil Deaver, a kindred spirit and another writer whose life was as pure a dedication to writing as to be a religious calling. The three of us had splendid times together and our friendship was the best thing to come out of my experience at Spalding. For that, I am forever grateful to Spalding. Bob wrote me once, “Oh Richard, I realize that when I write to you, I am trying to write us back to those evenings in Louisville we shared with Phil Deaver.” I never met two men I loved more.

I talked to Bob just a few days before he died. His voice was faltering, but he was still there, Bob Finch, the writer and curious spirit. Even weak, he was inimitable. He died a few days later and despite knowing he was on the verge, I was stunned. I still am. I feel less secure in the world now that he’s gone. And much sadder.

His writing will live as long as there are books and readers.

Beautiful, Richard. The worst part about getting older is not the wrinkles, it's losing those around us who we love. (Not whom or that, I checked.)

I will always be thankful to you for directing me to Bob. He was an exacting, but humorous mentor and a word of his praise was better than winning the lottery. He never failed to steer me in the right direction. I reread his books now and then to set things right in my world. Thank you for this moving tribute.