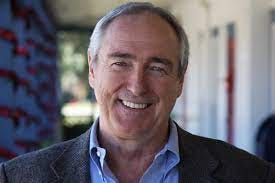

A little over six years ago, Phil Deaver died. He was 72. I think of him often, still. When I do, I summon up one of the sweetest men I have even known, full of good intentions and humor.

He was a great friend, loyal and caring. I can’t see and talk with the man again; but my memory can summon the times we spent together, the things he said and how he said them, and I am grateful for that. Good friends can leave their earthly selves, but their spirit stays with us and nurtures us, often in unexpected bursts, like sunshine.

Phil was a writer, first and last.

He was a complex man, and he wore his worries and insecurities on his sleeve. I remember him at Spalding University, in Louisville, where we both taught writing, how nervous he was among people there, how insecure, wanting to be with people he knew and trusted. He would insist on eating with just three or four people and no one else. You couldn’t help but love him and feel protective of him, he was so human.

Some of the writers who were our colleagues at Spalding were cliquish and condescending, and Phil was sensitive to any sense of judgment, imagined or real. Those writers, breezily haughty, probably do not know who they are, arrogance being the blinder it is, but I do. Fiction was not their genre, I can tell you that. They excluded an open heart, a lover of fiction and a man who had earned every accolade and advancement by pure passion and determination. Their loss.

Phil’s father and grandfather were killed in an automobile accident when he was 18, and that changed him forever and haunted him forever. He told me the story of that day many times, with a matter-of-fact solemnity to it, and I often felt I was there with him when he returned home that day to hear the news from his sister. This was the defining moment of his life, and it never was far from his mind or heart. He worshiped his father, who was a doctor in a small town in Illinois.

Phil was raised Catholic, and I don’t think he ever left his faith, despite what he might have claimed. It was deeply there. He had a sense of Catholic guilt about him. He told me that after his father died a group of Catholic elders from his town took him on a silent retreat. It meant a great deal to him.

He had a distinct way of talking, a Midwestern drawl with a slow cadence often leading to a bright punctuation of emphasis. I can still hear his voice in my mind’s ear. He was rooted in the Midwest.

Fiction was everything to him, a religion. He worshipped great fiction writers, especially living ones. Ann Beattie was a good friend. He loved Robert Stone and Richard Ford. He was a fiction writer to his very core. His first book, Silent Retreats, a book of short stories, won the prestigious Flannery O’Connor Award in 1988. (All underlined titles have links to the works themselves.) In all his writing, Phil shows a deep love and affection for his characters. That’s not always the case with writers.

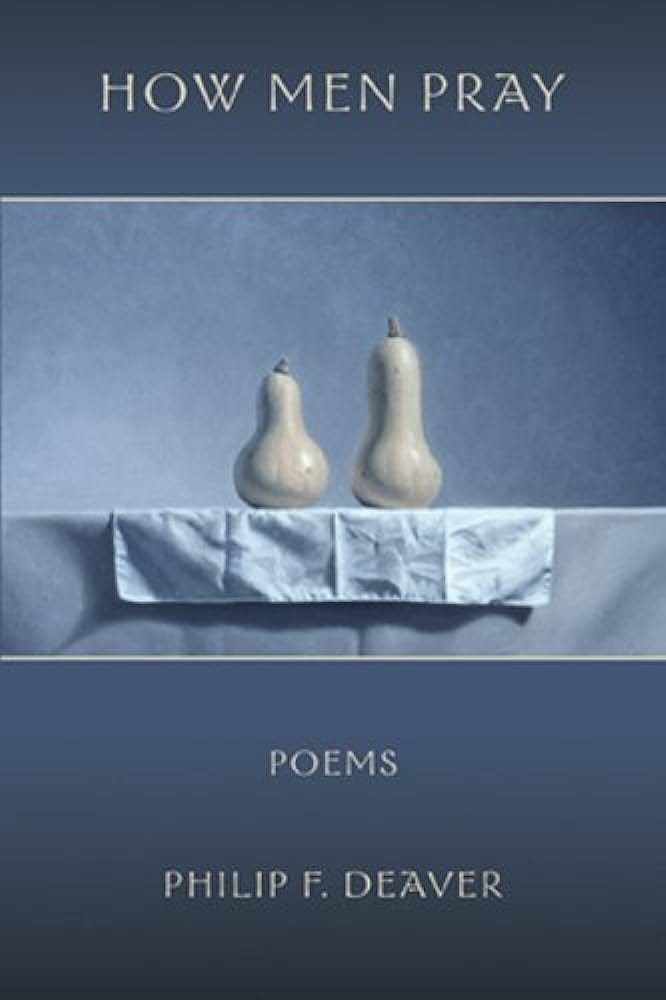

He published a book of poems, How Men Pray. I always thought he was a better poet than he thought he was or wanted people to think he was. I liked his poetry very much, and I remember how proud he was when Garrison Keillor chose his poems—on four occasions—to read on “The Writer’s Almanac.” Try his poem, “Illinois,” read by Keillor on June 29, 2014.

Phil also edited an anthology about baseball, Scoring from Second: Writers on Baseball. He was a serious fan of the game, among the sort who drive to spring training camps to see games.

I visited him twice in Florida before he became ill. I loved being at his home. We would sit and talk about books and writers and fathers and fatherhood and anything else that came to mind for hours. And watch baseball. He was a delight to be with.

He arranged a reading for me at Rollins College in Winter Park, Florida, where he taught and also at a local bookstore. The bookstore reading was lightly attended, and he was mortified. It didn’t bother me that much, having read at quite a few lightly-attended events in my time, but I know how he must have felt. I’ve arranged readings that were sparsely attended. You feel like you’ve let the author down. He hadn’t, of course. Part of the game.

Phil helped other writers, too. He did everything he could through Rollins to aid writers he admired or who he felt were deserving. I remember he brought in a young writer from New Orleans, who had been his student at Spalding, so she could meet with one of her literary heroes, Jamaica Kincaid.

This to me is what separates many writers from others. Those who, like Phil, use whatever influence and funds they have, not to mention encouragement, to help emerging writers flourish and those who claim they will help, and don’t. When Phil pledged his help, he kept that pledge. His students loved him. He was always enthusiastic about my work, in more ways than one, and that meant everything to me.

He and I used to play a ridiculous sort of game where we posed as 1950’s TV cowboy heroes. I was the Cisco Kid, and he was Lash LaRue. Which became simply, Cisco and Lash. We’d begin our letters to each other “Dear Lash” or “Dear Cisco.” It meant something to us—that 1950s TV culture that helped raise us in a dull dry era. It was some of the little romance America had back then. We still had the Wild West. We were intrigued by Lash. He used a bullwhip to subdue the bad guys. Think about it.

When I heard from Susan Lilley, his wife at the time, that Phil had suffered a brain disorder, and that, as she put it, the old Phil was slipping away, I wanted to visit him before he slipped away altogether.

So, I went to Florida in the spring of 2016 to see him for a few days. It was a sad trip. Part of him was indeed gone, and I think that may be one of the saddest things that can happen to someone we love, to have their corporal selves there, right before us, unchanged, but to have the self, or much of the self, missing. It didn’t make sense to me—there we were in his house where we had once laughed and bantered for hours—and I kept looking for Phil, the man who I loved and admired so much and who was a wonderful friend, to appear. But he was not to be found.

He was haunted by his Flannery O’Connor Award, weighed down by the burden of promise that honor bestowed on him and not producing another work of fiction. So, when he published a new book of short stories, Forty Martyrs, in 2016, a fine book, just a month or so before I visited him, he and all his friends and admirers were relieved and happy. His friend Ann Beattie loved the stories. Phil showed me a letter from her praising the book unreservedly, and he was hugely proud of that praise, which was so clearly sincere, as he should have been. I have an autographed copy. The dedication to his book reads,

In memory of my father,

Philip F. Deaver, M.D.

1920-1964

I’m writing about Phil, now, six years after his death, because in doing so, I focus him clearly and bask in his sweetness. I am better for that. For another reason, as well. When we no longer talk about someone, when we no longer conjure their laughter, the way they walked, spoke their words, the way they drove a car, sat and read a book, argued with us, laughed and talked about the things they loved—then we are co-conspirators in their vanishing.

I miss him. Twice I wished for him as mentor at Spalding, and twice my wish was granted. Those were the most productive writing seasons of my life because he insisted on new writing in each submission. He was so kind to me even while bearing down on my grammar. He also helped me find my next writing family by sending in a scholarship reference to the AWW at Hindman. And I attended that first year thanks to him, and then I went many times after. He made a huge and positive difference in my life because he heard my voice and defended it in workshops at Spalding. He understood the struggles of my life and helped me become brave enough to transform those into fictional stories worthy of reading. He was always available even after I left Spalding, to read something or help with a problem in a writing project. When I heard of his illness I wept profusely and wrote him a letter of gratitude for all he had helped me overcome. I didn’t know if at that point in his illness if he’d even be able to read it, but his family did read it to him and his son contacted me. I am glad you have honored his life with your words here. I miss Phil. When I remember him in Louisville , one of the best images imprinted in my mind is of you and Roy H. flanking him on either side heading up and down the sidewalks heading to and from classes or to the next meal usually talking and laughing and so glad to be together. In the spring there were showers followed by clean sunlight and every plant was blossoming and all the streets were shining. In the fall the light was golden and so were leaves on the trees. And moving through our midst were always the three of you, a constant, a powerhouse of the best writers. …yes, he is still very much with us who remember.

Appreciatively enjoyed this wonderful tribute!