From time to time I see people turning on their literary heroes. Writers who they used to praise to the skies, they now condemn in the harshest way. Ernest Hemingway comes to mind. Once esteemed and lauded, there came a time when he was rejected, even ridiculed. That’s still going on. Most of this condemnation I believe comes from people not approving of Hemingway’s life, his feverish pursuits of bullfighting, big game hunting, etc. I think at times it’s only marginally about his writing. I would bet some of the detractors haven’t read a word of what he wrote, or very few. I would also bet that some of these grand inquisitors actually admire Hemingway’s writing but feel that, for political reasons, they have to join the mob of ostracizers.

It’s easy to join the mob. It’s easy to bask in the sanctimonious pillorying of an artist when you’re part of a group effort.

“Why the Hell Are We Still Reading Ernest Hemingway?” is the title of a 2018 article in the Daily Beast.

It takes courage to say: I don’t agree with the mob. I stand by my love and admiration of this writer. Now and forever. Why? Because of the writing. Because it’s good. Because it always will be good.

It takes someone with guts and eloquence.

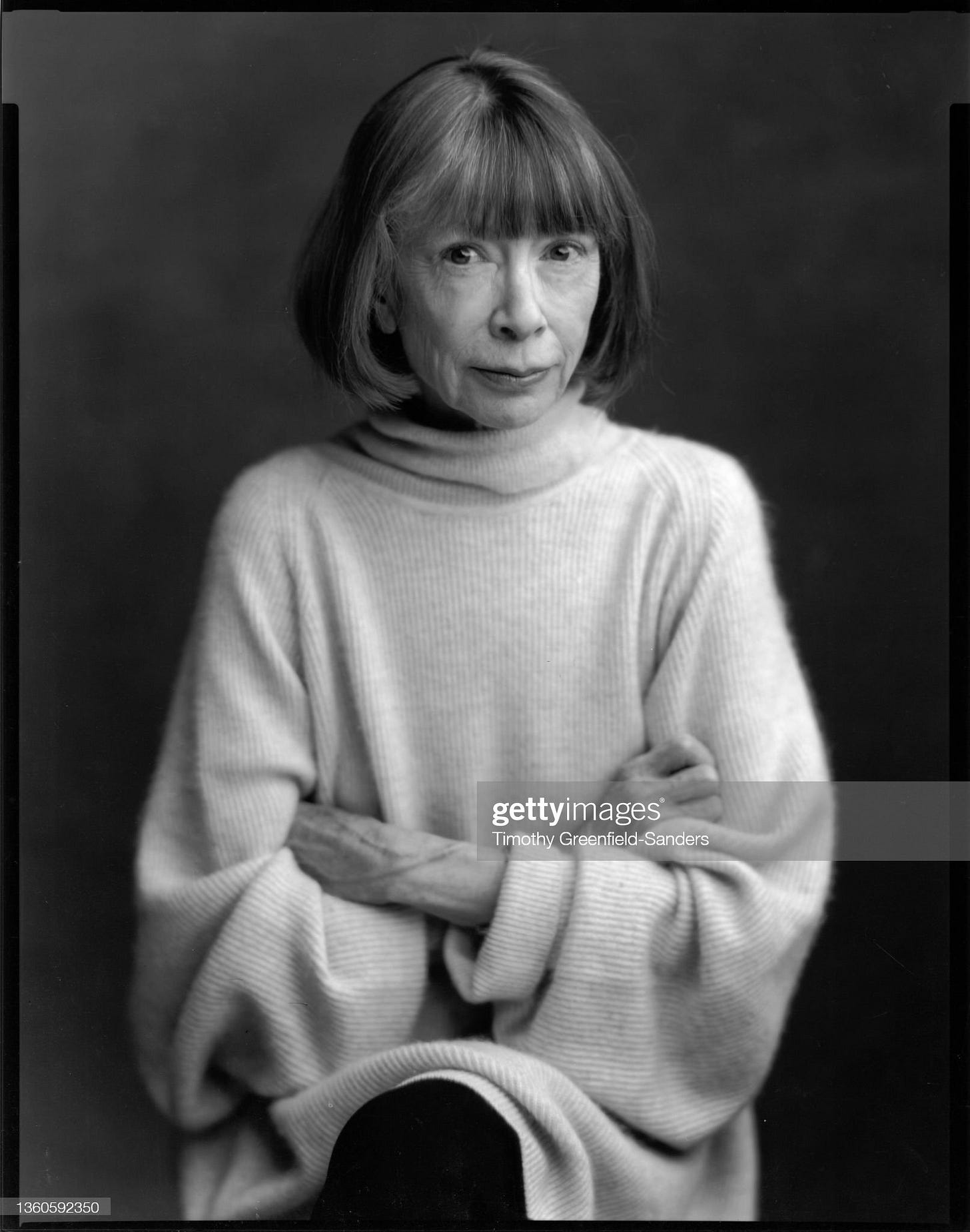

Like Joan Didion.

Didion wrote a powerful, unambiguous homage to Hemingway’s writing titled, “Last Words,” in the November 9, 1998 issue of The New Yorker. The essay is to a great extent about the effort to publish, posthumously, work by Hemingway that he did not approve for publication when he was alive. For a while, that became a cottage—or, better put, a skyscraper—industry with EH’s unfinished work. It was always about money, not literature. Didion takes those publishers and editors to task.

The essay is also about the power of Hemingway’s words.

Didion starts the piece by quoting the famous beginning to A Farewell to Arms:

“In the late summer of that year we lived in a house in a village that looked across the river and the plain to the mountains. In the bed of the river there were pebbles and boulders, dry and white in the sun, and the water was clear and swiftly moving and blue in the channels...”

Didion writes, “So goes the famous first paragraph of Ernest Hemingway’s ‘A Farewell to Arms,’ which I was moved to reread by the recent announcement that what was said to be Hemingway’s last novel would be published posthumously next year. That paragraph, which was published in 1929, bears examination: four deceptively simple sentences, one hundred and twenty-six words, the arrangement of which remains as mysterious and thrilling to me now as it did when I first read them, at twelve or thirteen, and imagined that if I studied them closely enough and practiced hard enough I might one day arrange one hundred and twenty-six such words myself.”

Is there a more clear, more straightforward expression of praise than that?

Didion was aware of the aspects of Hemingway’s outsized life that the mob objected to:

“We have seen the snapshots: the celebrated author fencing with the bulls at Pamplona, fishing for marlin off Havana, boxing at Bimini, crossing the Ebro with the Spanish loyalists, kneeling beside ‘his’ lion or ‘his’ buffalo or ‘his’ oryx on the Serengeti Plain.”

Nevertheless. Nevertheless, it’s the writing that counts in the end: “…we sometimes forgot,” she writes, “that this was a writer who had in his time made the English language new, changed the rhythms of the way both his own and the next few generations would speak and write and think.” She concludes, “This was a man to whom words mattered. He worked at them, he understood them, he got inside them.”

No summer literary soldier she.

What do I feel about Hemingway? I think he was a great writer who widened horizons for both readers and writers. I’m with Didion: he understood words. He used them with a precision that can still elicit awe. He taught me a great deal. I’m well aware, though, that some people will never like Hemingway, for whatever reasons. Does he have repellant passages and stands in his writing? At times, yes. I think of his far below-the-belt strikes at Gertrude Stein and F. Scott Fitzgerald in A Moveable Feast. But that’s simply not enough for me to turn my back on him.

The bigger point is: don’t abandon your literary heroes, writers you love, simply because the world turns against them.

It’s not just Hemingway, of course, who has had their door pounded on at midnight by the torch-bearing mob of those who would “correct” our literature.

David Denby put it well in a 2012 article about the great Ralph Ellison,

“The reputation of ‘Invisible Man’ has suffered no serious hits over the years. Yet Ellison’s reputation as a man is in very serious danger. Eventually, in our culture, where literature is of relatively little importance, and gossip and personality matter enormously, the book may come to suffer by association with the artist who created it.”

In a 2020 article in The New Yorker, “How Racist Was Flannery O’Connor?” Paul Elie declares that O’Connor’s remarks outside of her writing “belong to the author’s body of work; they help show us who she was.” Evidently, the work no longer speaks for itself.

Others may seek the safety in numbers of the politically correct. I hope I will always speak up, will defend my literary heroes when the horde goes after them. I hope I have the courage to follow the example of the stalwart Joan Didion.

I don't like the mob either. Morality police is how I would call it. I haven't read Hemingway in a long time, so I can't say how I'd feel about his work specifically.

Yet, this is how I'm relating to what you've written from my experience. It makes me think of Michael Jackson. After watching the documentary of the survivors of his sexual abuse tell their story, I can't enjoy his music. Whenever I hear it, I hear the voice of a rapist and I see images of those boys, of Michael molesting them, of how he hurt people and got away with it, and I feel physical pain in my chest.. and anger.

A song that previously made me happy and joyful, now makes me angry, because I know what the artist was doing while he was creating and I can't ignore that. Some people can.

My cousin loves his music and always will. My cousin says the art is not the artist. The art has its own life. That can be true. I see the beauty of that perspective. As an artist myself, I want that to be true - I want my art to be an entity in and of itself.

In this case, my cousin can hold the art and the artist separately. I can't. Maybe in another case, with a different artist, different art, and different vices, I'd be able to and my cousin wouldn't.

Like Hemingway, Michael Jackson revolutionized his field, and I continue to enjoy the music that has evolved from the developments he initiated. I am grateful for his contributions to the evolution of music, as I am grateful for Hemingway's contributions to literature. (So, so grateful!) At the same time, for me, in my body, Michael's own songs have become visceral reminders of harm.

For me it's not about jumping on a bandwagon or joining a mob, it's about how I feel. I imagine this must be true for at least some of Hemingway's detractors, no?

I think it's OK, great even, that many people can continue to appreciate the work, I think it's OK, great even, to be angry at the morality police, and I also want to acknowledge a third group, people whose sensitivities are too overpowered by the harm perpetuated by the artist to continue to enjoy the art.

I think these groups can coexist peacefully, and when we take a super wide lens perspective, I think we need them all. Does that resonate, or have I missed your point?

Thought-provoking topic, Richard! Thanks for sharing!

Well done Richard. I like to see this kind of push back when all the literary world gangs up on a good writer. And Hemingway is clearly that and all the admirable things you say about him. I love teaching one of my favorite Hemingway books, A Moveable Feast, but that text highlights the real complication of Hemingway's literary legacy. The writing is mostly pitch perfect. But there are chapters–like the one in which he expresses disgust at Stein's lesbianism, or his awful treatment of a gay writer in "The Birth of a New School," or his reprehensible evisceration of Fitzgerald's alleged sexual inadequacies (being dead F was unable to defend himself), that certainly justify the criticisms that some readers level at him. When my students read that book, and express their disdain for those chapters, they aren't piling on or joining the mob (they are blissfully unaware that such a mob exists), but telling me what effect the writing has on them.

I'm guessing, though, that your defense of H brackets this text, since it IS (ostensibly) his life and not a part of his fiction (though I seem to recall that he wanted it read as fiction). And if you think readers should separate a writer's life from his/her work, I guess we have to exclude their avowedly autobiographical texts from our assessment of them.